Most payer teams can stand up a prior authorization API.

They can:

- expose endpoints

- map basic request fields

- return approval or denial status

That part is doable.

The trouble starts after go-live, when providers begin using the API, and the data exposed through it has to match the reality of how prior authorization actually moves through the organization.

Many implementations look stable in testing but begin to drift once real requests start flowing across channels and systems. Providers see inconsistent statuses. Internal teams struggle to reconcile timestamps. Reporting numbers do not line up with operational dashboards. None of this usually comes from a failure to follow the FHIR guide. It comes from the underlying workflow and data capture.

Why prior authorization is different from other APIs

Unlike claims or eligibility, prior authorization rarely lives in one system. Requests can arrive through portals, EDI transactions, call centers, or delegated vendor platforms. Updates may be entered in utilization management systems, clinical review tools, or core administrative platforms. Each system captures events at slightly different times and with slightly different status definitions.

As long as these differences stay internal, teams manage them through manual reconciliation and operational knowledge. Once an API exposes that information externally, those differences become visible. Providers expect the API to reflect the current state of the request. If one system updates faster than another, the API can return outdated or conflicting information. This is where implementations begin to show strain.

What changes under the current CMS interoperability requirements

CMS expects prior authorization data shared through APIs to support transparency and reporting. That shifts the burden from simply exchanging data to proving that the data reflects reality. Status transitions need consistent definitions. Timestamps need to align with when events actually occurred. Requests initiated outside the API must still appear in the API’s history.

Teams that treat the API as a final integration layer often discover late that their workflow capture is incomplete. They then need to revisit status mapping, data sourcing, and reporting logic after the interface is already in use. This leads to rework and operational friction.

The more stable approach is to treat the API as a surface built on top of a clean, traceable workflow. That requires aligning systems and definitions before exposing data externally.

These expectations sit alongside broader CMS interoperability rule timelines for payers, which define when APIs must be operational and measurable.

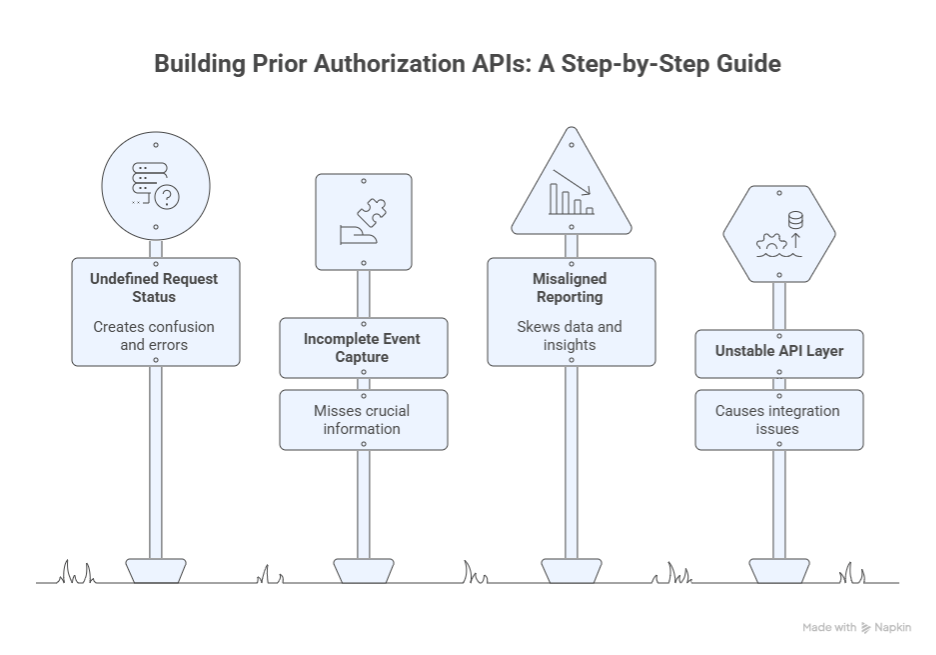

Where real implementations break

Prior authorization activity rarely follows a single path. Requests and updates move across intake channels, review systems, and vendor platforms, each with its own timing and status logic. When APIs expose that data externally, even small inconsistencies become visible to providers and internal teams.

CMS expects these APIs to support more transparent and reliable data exchange. That expectation depends on consistent workflow capture and status alignment across systems. The following areas are where implementations most often lose that alignment.

1) Status normalization across channels

Prior authorization has a basic promise: a provider wants a reliable status at any moment. The payer reality is different. Status lives across portals, EDI, UM systems, delegated entities, and manual intake.

What breaks first is not the endpoint. It is a status meaning.

A few examples that cause constant production disputes:

- Pending vs pended vs in review vs waiting on documentation. Different systems use different labels for the same moment in the workflow.

- A request that looks “approved” in one system because a clinical decision is recorded, but still “incomplete” in another because documentation requirements are not closed.

- Status changes that are entered late, so timestamps reflect data entry time rather than the operational event time.

When the API exposes those mismatches externally, providers assume the API is wrong. Then your team spends weeks patching mappings, adding exceptions, and trying to explain why statuses differ.

Spell out that the API requires a normalized state model that your internal systems may not have today. Do not call it a “nice to have.” Call it the prerequisite.

2) Event capture and traceability

Many payer teams build the prior authorization API assuming the request begins in the API. That is rarely true.

Even the Da Vinci PAS IG is explicit about today’s reality and why the industry is trying to move away from fax and manual transcription. The guide notes that fax-based workflows drive back and forth and require rekeying, which creates inefficiency and errors.

If requests start outside the API, you still need the API to represent the request lifecycle. That is where traceability breaks down.

Common failure patterns:

- A request begins by fax or phone, then later gets entered into the UM platform. The API only sees the UM record, and the first visible event is already midstream.

- Requests for additional information happen outside the main system or are recorded in free text. The API cannot show a coherent “what we asked for and when.”

- Resubmissions are treated as new requests in one system and the same request in another, so correlation breaks.

This matters beyond provider experience. CMS also ties the final rule to operational accountability and reporting. If you cannot reconstruct event sequences with consistent timestamps, you end up reporting something that is difficult to defend.

Define the minimum event trail your program must capture, then show how payers usually miss it. That is the kind of detailed decision that makers look for.

3) Attribution and access logic that influences what providers can see

Prior authorization APIs do not exist in isolation. The moment you put data behind APIs, access control becomes a business policy expressed in software. That is why provider access and attribution matter even when your blog is about prior authorization.

CMS states that impacted payers determine whether a provider has a treatment relationship with the patient using a patient attribution process.

What breaks in practice:

- Attribution logic built for value-based reporting gets reused for API access decisions, then fails for urgent care and specialist scenarios.

- Member plan changes or network changes create windows where the provider believes they should have access, but the payer system does not recognize the relationship yet.

- Opt out or consent policies exist on paper but are not enforced consistently across systems, so behavior differs depending on which system the API is pulling from.

Connect access disputes directly to program cost. Every access issue becomes an escalation. Escalations become operational drag. Drag becomes a hidden tax on the interoperability program.

4) Da Vinci PAS implementation guide reality

Competitors will mention PAS to sound credible. They rarely explain what PAS means in delivery terms.

PAS is not a single payload. It is a structured approach to prior authorization exchange. Even if you limit the scope, you still face mapping work, documentation handling, and workflow alignment.

The PAS guide itself is detailed and evolving, and it explicitly aims to enable direct submission of prior authorization requests from EHRs using a widely supported standard.

Where implementations break:

- Clinical documentation expectations do not map cleanly to what the provider can send digitally. Teams end up with partial digital submissions and manual follow-ups, which defeats the purpose.

- Code systems and coverage rules are represented differently across internal payer platforms. The same request looks valid in one system and incomplete in another.

- Payers underestimate the amount of testing required with real provider EHR workflows. API tests pass, but EHR-initiated transactions fail due to edge cases and documentation gaps.

Write this as an execution reality, not a standards lecture. The reader should leave understanding why “we support PAS” is not the same as “we can run PAS in production without constant manual correction.”(Da Vinci PAS implementation guide)

5) Delegated entities and vendor platforms

Delegation is normal in payer operations. It is also one of the fastest ways to create API instability.

What breaks:

- Delegated entities use their own workflow tools and status models. The payer core platform sees only a subset of events.

- Decisions are communicated through channels that do not feed back into the payer system fast enough to keep the API current.

- Identifiers do not match cleanly across delegated workflows, so correlation fails.

This is the point where many teams either accept an API that is incomplete or attempt complex data stitching that becomes hard to maintain.

Show that delegated workflows require explicit integration design and governance, not informal assumptions.

6) Production monitoring gaps

This is the silent killer. Teams treat the API as a build deliverable and do not design an operating model.

CAQH’s work on FHIR implementation challenges consistently points to barriers like competing priorities and the practical complexity of implementation.

Even when the endpoint is up, production success depends on day two capabilities.

What breaks after go-live:

- No correlation and tracing, so incidents take days to diagnose.

- No agreed ownership for provider-reported issues, so tickets bounce between IT, UM ops, and provider support.

- Retries and resilience are not tuned, so downstream slowdowns look like API failures.

- Status reconciliation is missing, so the API drifts from operational truth without anyone noticing until providers complain.

Make monitoring part of the implementation scope, not a post-launch enhancement. Many organizations begin addressing these issues when they expand prior authorization automation programs and discover that automation alone does not stabilize API behavior.

The build order that prevents rework

Teams often treat the prior authorization API as the final layer of an interoperability program. In practice, it works better when it is treated as a surface built on top of stable workflow capture and data alignment. When those foundations are set first, the API reflects operational reality and remains predictable after go-live. The sequence below reflects how many payer programs stabilize faster and avoid rebuilding core components later.

Decide what is authoritative before building the interface

The first step is not selecting an implementation guide or configuring an endpoint. It is deciding which system defines the current state of a prior authorization request at each stage. Requests and updates can appear in utilization management platforms, vendor systems, or manual intake workflows. If teams do not agree on a source of truth for status and timestamps, the API will mirror those disagreements externally.

This decision is usually handled through data governance and operational alignment rather than pure engineering work. It requires defining how systems reconcile differences and how updates propagate across platforms. Once the authoritative path is clear, mapping logic becomes easier to maintain, and reporting metrics becomes easier to defend.

Make prior authorization events traceable across channels

The API needs to represent the lifecycle of a request even when that lifecycle begins outside the API. That means requests entered through call centers or fax still need to appear with consistent timestamps and status transitions. The goal is not to eliminate alternate intake channels immediately, but to ensure that events from those channels are captured and normalized before they surface externally.

Traceability becomes especially important when reporting obligations depend on request timing and outcomes. If the event trail is incomplete or inconsistent, teams spend time reconciling data rather than improving the workflow. A clear event model and consistent timestamp logic help the API remain aligned with operations over time.

Design measurement and reporting alongside the API

The current regulatory direction ties interoperability work to transparency and reporting. That means measurement cannot be added at the end. Teams need to define how they count requests, decisions, and timing metrics while the workflow and mapping rules are still being finalized. Once those definitions are stable, instrumentation can be built into the API and supporting systems.

When measurement is designed early, reporting tends to align with operational dashboards. When it is added later, teams often find that they cannot explain discrepancies without revisiting mapping rules and data sources. Designing reporting and API behavior together helps avoid that rework.

Stabilize the operating model before scaling usage

After go-live, the API becomes part of daily operations. Providers use it to check status and submit requests. Internal teams rely on it for visibility. At that point, the focus shifts from building to operating. Clear ownership for incident response, provider inquiries, and mapping changes keeps the interface predictable. Monitoring and tracing help teams diagnose issues quickly and keep data aligned across systems.

Programs that define this operating model early tend to scale more smoothly. Programs that treat it as an afterthought often spend their first months after launch adjusting mappings and responding to escalations. Stability comes from treating the API as an operational service rather than a one-time project.

What payer leaders should focus on now

For payer organizations preparing for upcoming interoperability expectations, the immediate priority is alignment across teams and systems. Utilization management, compliance, digital platform teams, and data governance groups all influence what the API ultimately exposes. Bringing those groups together to define status meaning, event capture, and reporting logic early helps prevent surprises later.

It is also useful to test workflows using realistic scenarios rather than only clean test cases. Requests that arrive through multiple channels, require additional documentation, or involve delegated review often reveal gaps in mapping and attribution. Addressing those gaps before external use increases confidence when the API begins handling real traffic.

Programs that move in this sequence usually spend less time revisiting foundational decisions and more time improving performance and provider experience. The effort invested in aligning workflow truth early tends to reduce friction once the API becomes part of routine operations.

Stabilizing prior authorization APIs usually requires alignment across workflow, data ownership, and monitoring before usage scales. That is where many payer teams pause and reassess their interoperability approach.

How Can We Help?

If your team is preparing to implement prior authorization APIs but wants to avoid building an interface that looks complete and then becomes difficult to stabilize, the starting point is an assessment of workflow capture, status alignment, attribution logic, and reporting design. Most rework happens when these decisions are made after the API is already in use.

A focused interoperability review should produce three outcomes: clear decisions on where prior authorization data is authoritative, a sequencing plan that aligns mapping and reporting before external exposure, and an operating model that keeps the API reliable once providers begin using it at scale.

Explore our healthcare interoperability solutions to see how payer programs prepare for prior authorization APIs and broader CMS interoperability requirements. You can also request a readiness discussion or contact us at info@nalashaa.com.