People are calling this an “API rule,” but that framing causes payers’ trouble.

APIs are the visible output. The hard part is everything behind them: where prior authorization activity is captured, how statuses are normalized, who owns the provider directory truth, and how access is controlled when members change plans or providers. CMS 0057 F forces those hidden issues into daylight, because the rule is designed to make data usable across patients, providers, and payer-to-payer exchange, while also pushing transparency around prior authorization.

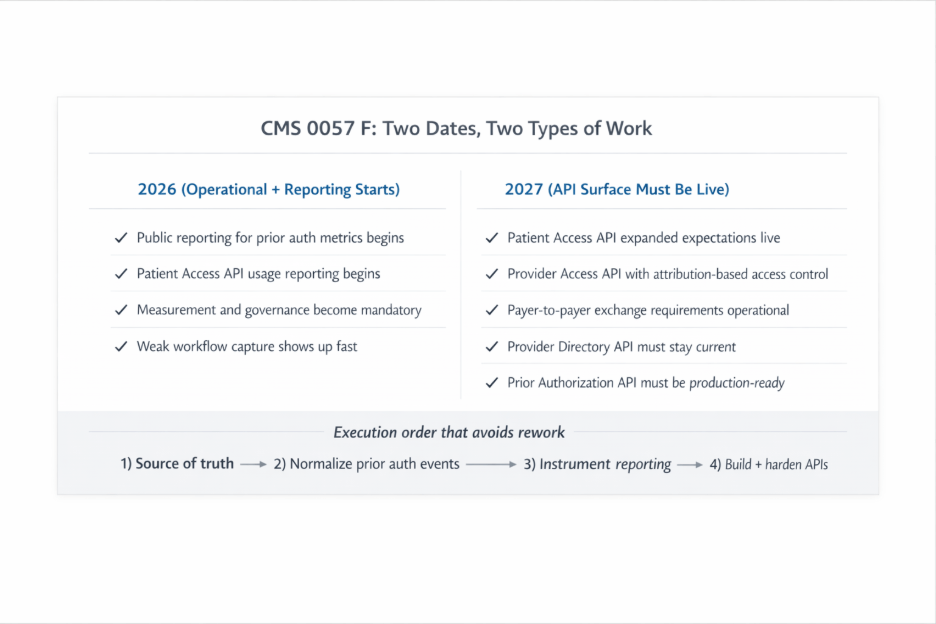

Two dates shape the program.

January 1, 2026, is when the operational and reporting clock starts. CMS requires impacted payers to publicly report certain prior authorization metrics annually, with the initial set due March 31, 2026. CMS also requires annual reporting related to Patient Access API usage.

January 1, 2027, is when the major API requirements must be implemented and available.

If you want this to be smooth instead of painful, the sequence is straightforward: decide what data is authoritative, make prior authorization activity traceable across channels, and then build the API surface with monitoring and reporting designed into the foundation.

Why does this rule change interoperability for payers

Interoperability programs inside payer organizations rarely fail because teams cannot build APIs. They fail because the “truth” of the workflow is scattered.

Prior authorization is the best example. Requests come in through multiple channels. Updates happen in different systems. Delegated entities and vendor platforms introduce their own statuses and timestamps. Meanwhile, provider and member relationships that govern access live in contracting systems, network systems, and attribution logic that is often tuned for billing and operations, not for API-ready data sharing.

CMS frames the final rule as a continued push to advance interoperability and improve prior authorization processes, with an explicit goal of reducing burden while improving access to health information across the ecosystem.

So for payers, CMS 0057 F becomes less about “standing up endpoints” and more about proving something harder: that the data you publish reflects reality, that you can explain how it was produced, and that you can operate the interoperability surface predictably over time.

Who this applies to and why ownership is the real blocker

CMS describes these requirements in terms of “impacted payers.” If your payer program is in scope, you carry accountability for both the API requirements and the reporting and operational obligations described in the rule and fact sheet.

Inside the payer organization, the work touches teams that usually do not operate as a single unit:

Compliance interprets requirements and defines what gets published and how reporting is handled.

Utilization management owns the prior authorization workflow, including what counts as received, pending, requested, approved, denied, or withdrawn.

Digital and platform teams own the API layer, identity and access, security controls, performance, and uptime.

Provider directory owners handle a data supply chain that spans credentialing, contracting, delegated entities, and periodic updates.

Data governance decides what is authoritative when systems disagree and how mapping rules change over time.

This is the part most teams underestimate. CMS 0057 F pushes these owners into alignment because the APIs and the reporting requirements remove the ability to keep “local truths” hidden inside individual systems.

The timeline that matters: what changes in 2026 versus 2027

A lot of competitor content collapses the rule into one big deadline. That creates bad planning behavior. It encourages teams to delay until late 2026, then scramble.

A better way to think about it is: 2026 introduces operational transparency and reporting accountability, while 2027 is the point where the full API surface must be live.

What starts in 2026

CMS requires impacted payers to publicly report certain prior authorization metrics annually, starting with compliance beginning January 1, 2026, and the initial set of metrics due March 31, 2026.

CMS also requires impacted payers to report annual Patient Access API usage metrics, which is not a small detail. It changes how you design the program because measurement cannot be bolted on at the end. You need clear definitions, instrumentation, and governance for how usage is counted and reported.

If you treat 2026 as “just reporting,” you create rework. Teams often discover late that they cannot measure what they are publishing, or they cannot confidently explain why the numbers look the way they do. That usually traces back to weak workflow capture and unclear ownership.

What must be live by 2027

CMS states that the final rule requires impacted payers to implement the major API requirements by January 1, 2027.

This is where the scale becomes obvious. Payers are expected to support multiple access patterns across patients, providers, and payer-to-payer exchange, plus prior authorization-related transparency provisions that depend on clean internal data.

If you start API build work without cleaning up data sourcing and workflow capture first, the APIs may technically work, but they will not survive real use. Provider disputes, patient complaints, reconciliation errors, and operational escalations will pile up. That is the “integration looks done but never stabilizes” scenario that payers want to avoid.

What CMS is requiring at a high level

CMS 0057 F finalizes a set of requirements aimed at increasing interoperability and improving prior authorization. Across CMS materials, the requirements land in a few broad buckets:

Patient access and transparency: patients must be able to access more complete information through the Patient Access API, and payers must measure and report usage.

Provider access: Providers must be able to access payer-held data for patients, which forces payers to operationalize access control based on treatment relationships and attribution logic.

Payer-to-payer data exchange: CMS finalizes a patient permission approach for payer-to-payer exchange and requires plain language educational resources explaining the benefits and how patients can opt in or withdraw permission.

Provider directory: Payers must support a Provider Directory API, which is often underestimated because directory data tends to be fragmented and difficult to keep accurate.

Prior authorization improvements and metrics: payers must improve prior authorization transparency and publicly report metrics annually, beginning with initial reporting due March 31, 2026.

That is the full shape of the program. It is a compliance-driven operating model that runs across data, workflow, identity, reporting, and production support.

The required APIs, explained the way payer teams implement them

Once you accept that CMS 0057 F is an operating model shift, the API list stops feeling like “five endpoints.” Each API pulls a different part of the payer stack, and each one exposes a different kind of weakness. Data gaps, unclear ownership, missing workflow capture, weak access controls, or an API layer that runs fine in test and collapses under real usage.

CMS groups the API policies around improving access to interoperable patient data for patients, providers, and payers, while reducing the burden tied to prior authorization. (CMS fact sheet)

Patient Access API

This is where many payers assume they are “already covered” because they did work after the 2020 CMS interoperability rule. CMS 0057 F raises the bar by pushing more meaningful transparency, including prior authorization-related information and the expectation that you can measure and report usage.

In delivery terms, Patient Access API work tends to break down into two parallel efforts.

One is the data assembly problem. Claims and encounters are usually manageable because there is already a pipeline. Clinical elements and USCDI-aligned data are harder because they often come from multiple sources or arrive late through partners. Prior authorization information is the hardest because the workflow itself is fragmented. If a prior authorization request comes in by fax or phone, the system might capture the decision but miss the original timestamps, documentation requests, or intermediate statuses. That is the gap that shows up in member experiences as “why does the app show nothing?” or “why is the status wrong?”

The second effort is instrumentation. CMS requires annual reporting related to Patient Access API usage, which means you need consistent definitions for what counts as a user, what counts as an access event, and how to separate testing traffic from real usage.

Provider Access API

Provider Access API is where access control becomes real. Patients are not the ones pulling data through an app. Providers are, and the payer is responsible for deciding which providers are allowed to see which patient data.

CMS describes a core mechanism here: impacted payers determine whether a provider has a treatment relationship with the patient using a patient attribution process. That attribution step is what keeps data sharing limited to appropriate providers. (CMS Provider Access API FAQ)

In implementation terms, Provider Access often runs into three friction points.

First is attribution itself. Many payers have attribution logic built for value-based care reporting or network management, but it is not always built for near-real-time access decisions through an API. Teams end up debating what counts as “current,” how far back a treatment relationship should extend, and how to handle edge cases like urgent care and specialists.

Second is opt out. Even if your technical access checks are correct, you still need an operational way to respect member choices and ensure systems enforce those choices consistently.

Third is external support readiness. When a provider cannot access data, who resolves it? Utilization management. Provider operations. Digital platform. Compliance. If you do not define this, the API becomes a help desk problem the moment it sees adoption.

Payer to Payer API

This is the API that sounds clean in theory and gets messy in the middle. It is tied to patient movement across plans and continuity of information. CMS also pairs payer-to-payer exchange with patient permission and patient education expectations, so it comes with workflow requirements beyond the endpoint.

Where payers get stuck is rarely the endpoint itself. It is data packaging and provenance questions. Which data is included? How far back does it go? How do you handle data that came from delegated entities? How do you explain gaps in the record without creating legal risk? This is also where governance becomes non-negotiable, because payer-to-payer exchange forces a more explicit answer to “what is authoritative.”

Provider Directory API

Provider directory work is usually underestimated because payers already have directories in some form. The compliance problem is not “do you have a directory?” It is “can you publish an accurate directory through an API, keep it current, and resolve disputes when systems disagree.”

This API pulls from credentialing, contracting, delegated networks, provider ops, and sometimes external directory vendors. The failure pattern is consistent. One system updates an address, another updates a phone number, a third updates network participation, and the API publishes an inconsistent mix. Then, provider abrasion starts because providers feel the consequences immediately.

If you want this API to survive, you need a directory supply chain, not a directory database. That includes update cadence, validation rules, exception handling, and clear ownership for dispute resolution.

Prior Authorization API

This is the most visible pressure point of the rule because it sits directly on the provider-payer relationship. CMS positions the final rule as reducing burden through improvements to prior authorization practices and data exchange, and the Prior Authorization API is one of the ways payers are expected to modernize that exchange.

At a high level, this API forces a payer to expose prior authorization status and decision information in a standardized way and support a cleaner exchange flow. The technical build is rarely the hardest part. The hardest part is making sure the API reflects the true workflow across all channels and delegated pathways, and that denials and requests for additional information are represented consistently.

In most payer environments, the fastest way to reduce rework is to strengthen workflow capture first, which is why prior authorization automation becomes a foundational move before exposing API level transparency.

The build order that keeps this from turning into a rework cycle

Most payer teams do not miss timelines because they picked the wrong technology. They miss timelines because they start building the API layer before the organization agrees on what truth looks like across workflows.

Here is the build order that keeps the program stable.

Decide what is authoritative, API by API

Start by mapping sources of truth for each API. Not a generic inventory. A clear answer to which system is authoritative, which systems contribute secondary fields, and what happens when systems disagree.

Directory and prior authorization immediately surface as the toughest areas, because the truth lives in multiple systems by design. If conflict rules are not decided early, your API becomes the place where different teams argue about whose data is correct.

Claims and encounters often have the most mature pipelines, but even those pipelines need clean ownership and reconciliation, which is why healthcare claims data integration is still a foundational part of the Patient Access API story.

Make prior authorization traceable across channels

Before you expose prior authorization-related information, make the workflow traceable.

If a request begins by fax and is later entered into a UM platform, can you reconstruct a consistent timeline? When was it received? When was additional information requested? When was that information received? When was a decision made? When was it communicated?

If you cannot, your API output will be incomplete, and your reporting will be fragile. Delegated entities magnify this problem because they introduce variability in how statuses and timestamps are captured.

The practical fix is to normalize the event trail. Status values, key timestamps, and identifiers that let you correlate a request across channels. You want that layer in place before the API surface is treated as finished.

Build measurement and reporting early

Because reporting begins in 2026, instrumentation has to be part of the design. CMS calls out annual Patient Access API usage metrics reporting and public reporting tied to prior authorization metrics.

Measurement design should cover what counts as a user, what counts as an access event, how to exclude internal traffic, and how to generate repeatable annual reports. Without that, reporting becomes a scramble, and metrics become difficult to defend.

Lock access controls and opt-out handling for provider access

CMS expects provider access to be scoped to a treatment relationship using attribution processes. (CMS Provider Access API FAQ)

That expectation forces explicit policy decisions. How do you define a treatment relationship in system terms? How often are attribution updates? How opt-out is stored and enforced. How do you audit access? Who resolves disputes?

If you leave those as informal assumptions, provider access becomes unstable after go-live because the disputes are about policy, not code.

Treat the directory like a supply chain

Provider directory success is largely operational. Update cadence, validation, exception handling, dispute ownership, and reconciliation across source systems. If you do not treat it like a supply chain, the API becomes a public mirror of internal inconsistency.

Operate APIs as production services

By 2027, endpoints must be live. More importantly, they must stay reliable.

That means uptime monitoring tied to ownership, tracing that makes debugging possible, resilience when downstream systems are unreliable, and a support model for external consumers. Without that, you end up with the familiar pattern where an API exists, but the organization cannot keep it stable.

A practical execution roadmap that payers can run

The easiest way to avoid panic later is to front-load the decisions that create rework.

In the first phase, confirm scope, map source of truth for each API, assess prior authorization workflow capture across channels and delegated entities, define reporting and measurement requirements, and make initial attribution and opt-out decisions for provider access.

In the second phase, build the normalization layer for prior authorization activity, begin directory reconciliation and validation, implement one API end-to-end with monitoring and instrumentation, and define support and incident ownership.

In the final phase, scale across the remaining APIs, harden access control and audit, onboard consumers in a controlled way, and operationalize governance for ongoing changes.

How Can We Help?

If your team is trying to meet CMS 0057 F without creating a fragile API layer that never stabilizes, the starting point is a readiness review that covers data ownership, workflow capture, access controls, and reporting design, not only technology selection.

A strong interoperability assessment should produce three outcomes: clear source of truth decisions, a sequencing plan that prevents rework, and an operating model that keeps the APIs reliable after going live.

Explore our healthcare interoperability solutions and request a readiness assessment for CMS 0057 F. You can also contact us at info@nalashaa.com.